Transformative Educational Leadership Journal | ISSUE: Fall 2017

If we believe changing outcomes for students depends on teacher learning, then we must cultivate a culture of learning in our schools. In doing so, a leader’s focus shifts from managing the building to designing learning environments in which the adults move from being employees to being learners. Here is how one school made this shift.

By Barb Hamblett

What’s needed are eyes that focus with the soul.

What’s needed are spirits open to everything.

What’s needed are the belief that wonder is the glue of the universe and the desire to seek more of it.

Be filled with wonder. (Wagamese, 2016, p. 105)

Introduction

We are living in a rapidly changing world. There is an urgent need to develop, within our students, the capacity to embrace a world full of wonder, curiosity and openness; to actively participate in making the world a better place. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports that “facing unprecedented challenges and opportunities, this generation requires new capacities,” (2017, p. 1) which include wonder as a natural way of being. Students will also need to have “open and flexible attitudes as well as the values that unite us around our community” (OECD, 2017, p. 1).

British Columbia’s Ministry of Education (BC MOE) recognizes the need for innovation in our schools and has published a redesigned curriculum focusing on big ideas, a shift to inquiry pedagogy and a focus on Core Competencies of Critical and Creative Thinking, Communication and Personal and Social Awareness (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2015) in all subjects and grades. Many educators have yet to internalize this new pedagogy into their hearts and minds. For example, Social Studies 11 teachers may shift the focus from European history to Asian or political studies, but this is still the “what” of teaching. Regardless of the course content, there is an important question to be asked. Are we able to say with confidence that students exiting this course have developed, “social and emotional skills as well as values like tolerance, self-confidence and a sense of belonging,” (OECD, 2017, Introduction) needed to thrive in a rapidly changing world?

When we discuss building self-confidence, or guiding students to become personally and socially aware, the “what” of teaching becomes less important. The content becomes the means to a greater end, focusing teacher planning on creating learning environments that

These environments put learners at the centre and ensure a more holistic approach to education (OECD, 2015). To achieve this type of environment, educators need support. Le Fevre, Timperley and Ell (2016) would agree; “As approaches to developing the knowledge and skills of students alter with curriculum change, so, too, does the need to change approaches to the development of teachers so they can teach students in these new ways” (p. 9).

The BC MOE mandates that students self-assess at least one of the Core Competencies (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2015) on the final school year report. For students, this requires capacities beyond memorizing content. Many are challenged when asked to reflect on their learning unless they have been given opportunities to practice reflective thinking. To begin with, a deeper awareness of their own thinking is needed, and students will require guidance on how to communicate effectively in order to make meaningful connections between the competencies and what they are doing in their classes.

When educators are asked to consider different pedagogies, they require professional learning that deeply examines how students learn. Core Competencies cannot be assessed or measured the same way content knowledge has been in the past. We need to be constantly curious about our students’ learning, requiring what Le Fevre et al. (2016), refer to as teachers’ adaptive expertise, the ability of teachers to inquire into their practice and use evidence to make decisions about ways to change the practice for the benefit of student learning, an ingredient critical to transformative pedagogical change.

If we believe that changing practice depends on the acquisition of new learning, then we must cultivate a culture of learning in our schools. In doing so, a leader’s focus shifts from an emphasis on managing the building to managing learning environments in which the adults move from being employees to being learners. As school leaders contemplate creating conditions to build communities of curiosity with their staff, they will also become more acutely aware of their own professional learning needs and those to model learning to the staff.

Shifting a school in this way can be witnessed through my own journey as a school principal; filled with success and failure, this example is testimony to just how complex the work of transformative change can be.

Ten Months of Work in a Large High School: Beginning with Alignment

When I tried to move forward with innovative change, I was interested in exploring the “bigger picture, to look at the interrelationships of [my school] as opposed to simple cause-effect” (Kools & Stoll, 2016, p. 17). I was curious to uncover what connections existed between the Leaders’ Group, (eight teachers tasked with leading instructional initiatives in the school), the professional learning communities (Dufour, 2004), and monthly staff meetings.

I sought to understand teachers’ interpretation of the roles of school Leaders and the PLC groups and, in turn, what PLC work looked like and how it was connected to the classroom. During this discussion, staff emphasized that topics explored at the PLC level were teacher-driven. They felt this time was their own to focus on collegial sharing and unpacking the new curriculum. They did not see a direct connection between the work being done in the PLCs and Leaders’ Group. The leaders, they said, predominantly worked through quantitative school data used to develop the school’s plan which could shape PLC explorations but did not have to.

In further conversations with teachers I did not see evidence that the PLC network was truly “responsive to the particular needs of students… [or] responsive to teachers’ needs in relation to their students’ needs” (Le Fevre, et al., 2016, p. 10). This is something Le Fevre et al. (2016) point out as a necessary characteristic of an effective professional learning environment. I also discovered there wasn’t an obvious correlation between topics explored in the PLC groups and student improvement. The space for teachers to be curious, to discover what was going on for their learners existed; however, they needed some guidance to introduce “a strong metacognitive element… to question their assumptions, test the veracity of them and change them when necessary” (LeFevre et al., 2016, p. 14).

In a staff of over 50 teachers, there were eleven PLC groups. We first made our learning visible through an online, shared document. As Kools & Stoll (2016) outline, technology can be a way to enable collaborative learning, and “provide the opportunity both to further the life of existing communities and to create new learning communities by connecting people and enabling them to explore and share practice” (p. 42).

We also tried to define our collective purpose. This was necessary to guide the PLC groups. because “in order to promote organizational learning, a vision needs to be meaningful and pervasive in conversations and decision-making” (Kools & Stoll, 2016, p. 36). Achieving this would prove difficult, however, with both the school and district strategic plans still in development; we simply did not have a strong vision yet. In response to the need for alignment, we turned to the spiral of inquiry as a way to develop a mindset of curiosity, encourage professional learning and take action (Halbert & Kaser, 2013). Even without a vision to unite us, the spiral provided a standardized framework for my staff.

From this structure, we emphasized two elements: scanning and professional learning. Even if teachers had already embarked on a journey that had not started with scanning, I asked that they gather evidence from their students as to what was going on for the learners. I hoped this information would ignite curiosity and build a learner-centered focus for the PLCs.

With the scanning evidence in hand, I believed teachers could identify their learning needs. According to Halbert & Kaser (2015), “the professional learning focus often emerges organically from testing out the hunches about what is leading to the situation for learners” (p. 53). Through shared digital means, my job would be to provide guidance to make sure their “new learning focus was likely to be of maximum value… [as opposed to] just jumping at a strategy or resource because it is available” (Halbert & Kaser, 2015, p. 54).

The entire spiral of inquiry was shared with the staff with a Google Slide Deck. I facilitated the process of colleagues seeing each others’ thinking and we began to see common threads emerging. Ritchard, Church and Morrison (2001) outline a number of ways to make thinking visible and point out that when we insert a thinking routine it becomes “an ongoing process of development in which the [leaders] and the [teachers] expectations and ideas about learning shift and deepen over time” (p. 262). Although the focus in each group continued to be different, we were beginning to align ourselves through the structure of inquiry.

Walking the Talk: The importance of moving forward together

Despite the best of intentions, I wasn’t clear how student outcomes were being affected. Little scanning evidence was recorded in the Google Slide Deck and even less evidence of professional learning was documented. I wondered if this was because of the technology and I also wondered whether leading by example would help. I demonstrated my willingness and commitment to work through the framework. Observations by McGregor et al. (2017) about leadership at the district level resonated with me, “District leaders need to put first their identities as learners themselves – openly and transparently – if they are going to truly ignite commitments to learning and accelerate the processes of innovation in their own educational jurisdictions” (p.21). With this in mind, I worked through the School Plan using the spiral framework and together as a staff we uncovered, through a number of scanning techniques, a plan that would guide us over the next few years. Although late in the year, we now had a co-constructed vision, something that was missing when we started this journey.

While we were making good progress with the School Plan and recording the process in the Slide Deck, the same could not be said for the PLCs. Some teachers expressed concern that they did not really know how to place their current work into the slide deck. For example, one group was exploring the use of Learning Maps. They used the book Rethinking Letter Grades (Cameron & Gregory, 2014) to build assessment documents for units of study that provided students with clearer learning targets and a more holistic approach to finding out what students knew. This group said they struggled with what they were supposed to put in to each section of the spiral Slide Deck. They questioned how scanning was involved in their exploration when they had already chosen a topic of interest? Their learning consisted of guidance from the book, Rethinking Letter Grades, so what else should they be recording on the slide for professional learning? When asked why they chose to explore Learning Maps, collectively they indicated it would help to make assessment more accurate and provide more useful feedback to students. They may be correct with this hunch, but without responding a need identified by scanning the students, they struggled to find out whether they had made enough of a difference after they took action.

I began to wonder about the shape of conversations at the PLC level as well. In order to examine this more closely, I joined the PLC group consisting of student support services and counsellors. The group members may have different roles, but they all focus on the most vulnerable learners. We began our scan by looking at failure and attendance rates, then anecdotal evidence from counsellors who shared what students were telling them about struggles at school. As a group we built a hunch that perhaps some of our students were experiencing learned helplessness and we were curious about whether our students were aware of the “correlation between mindset and academic attainment” (Reynolds & Birdwell, 2015, p. 21).

With this in mind, the group co-constructed a scanning tool to find out more about students’ growth mindset. This PLC group began to demonstrate some characteristics of an effective professional learning environment outlined by LeFevre et al. (2016). It was becoming “responsive to the particular needs of students and… responsive to their own needs in relation to their students’ needs” (LeFevre et al., 2016, p. 10). They were seeking out literature by Carol Dweck (2016), and using online resources like from Mindsetkit to shape their plan of action (mindsetkit.org, retrieved 2017).

I wondered if this group had accelerated their learning because, unlike the School Plan process, I was an equal participant at the table of learners. In other words, was this occurring because the leadership was more distributed, and if so, I wondered how I could recreate that experience with other PLCs. I also wondered whether my knowledge about the inquiry process at the table was the piece they had needed. Questions still remained about whether the digital template was a help or hinderance to working through a spiral of inquiry. I eventually consulted the teachers to get their thoughts about their challenges and successes this year in PLC as well as their feedback on the Spiral Slide Deck. The results of the survey will be mentioned later.

Keeping the Main Thing, the Main Thing – A Return to Scanning

In response to my concern over stalled progress in the PLCs, I invited a focus group to scan students. Seven teachers were involved and within a few weeks we had managed to survey just over 230 of our students using the four key questions outlined by Halbert & Kaser (2015) in Spirals of Inquiry: For Equity and Quality. These questions are a way to ignite the inquiry process so perhaps returning to them would help to refocus all of us. “Hundreds of BC educators have… made transformative shifts in their learning and teaching repertoires after exploring the experiences of their learners through posing and then reflecting on the learner responses to these questions” (Halbert & Kaser, 2013, p. 37).

1. Can you think of two adults at school who believe you will be a success in life?

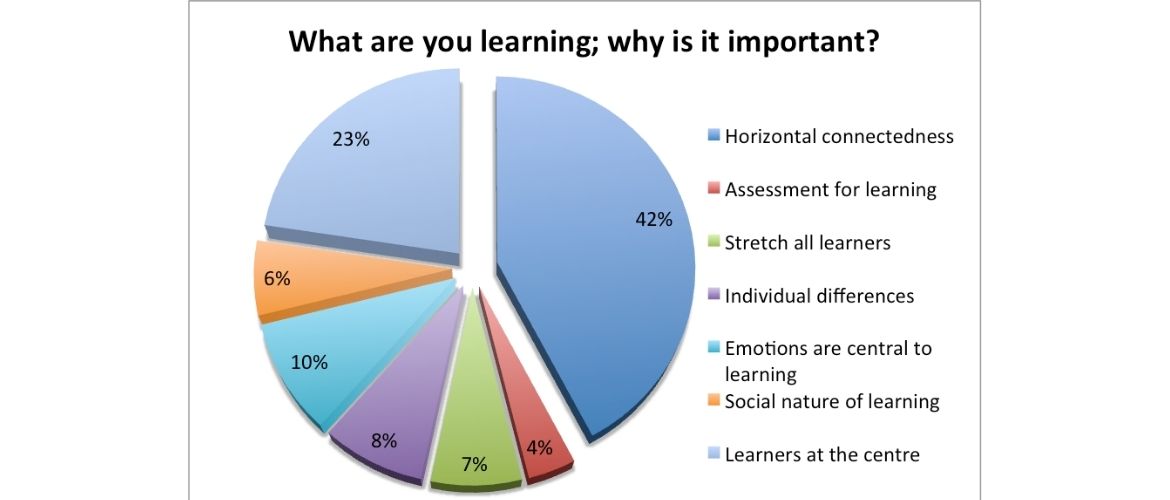

2. What are you learning and why is it important?

3. How is going with your learning?

4. What are you next steps?

Six hundred and ninety pieces of anecdotal information was collected revealing how the learning was going for students. The process of gathering the evidence was a positive experience in itself, however, sorting through the data and collating it into broad themes posed a challenge so we connected student information to the OECD Principles of Learning (2012). Time was spent on ensuring the team learned about the principles, then we attached the Principles to the evidence. In doing this, student information was revealed in a positive more broader context.

This exercise enabled teachers to connect personally and passionately to the principles. They negotiated with each other about where the student data fit, and regardless of which principle was attached to each piece of evidence, teachers were really listening to the student voice and they were really thinking about learning environments. We discovered that 30% of our students said they could not name two adults in the school who believed they would be a success in life.

| “Programming is important because that is the direction a lot of jobs will be heading in the future with the advances of AI and robotics”. (Gr. 11 student) |

Figure 3 Collated findings sample from the Key Questions which are connected to the OECD principles of learning (OECD, 2012) When we asked students what they were learning and why it was important, well over half of students told us that seeing connections between what they were learning and life beyond high school was important to them. This led to more questions like Am I making my learning intentions clear? Am I checking frequently enough to ensure my students are seeing relevancy in what they are doing in class? In turn, the OECD Principles of Learning (2012) became a touchstone for where we needed to journey next.

Some Emerging Themes

The past ten months at this school has provided a look into what goes into shifting a school towards a culture of curiosity. I saw my learning shaped in direct response to my staff ‘s needs. As I encountered challenges, I sought help and advice from colleagues, learning partners and experts, all of whom challenged my thinking, valued my reflection and redirected me to more new learning. I also immersed myself in educational theory, scanned my staff constantly and tweaked my action plan in response to what was occurring around me; what I previously referenced as adaptive expertise. LeFevre et al. (2016) suggest adaptive expertise “is driven by a holistic inquiry mindset, underpinned by curiosity, responsiveness, and willingness to learn and change” (p. 9).

The idea that teachers are learners has remained at the forefront of my thinking. Staff meetings have become learning environments with clear targets to help us understand the relevancy of what we were working through. Although this challenged people’s beliefs and required constant revisitation to explain why this change had occurred, it was one of the strongest ways I could demonstrate my commitment to the importance of our collective learning.

I have also realized the power of sharing a common language, something we accomplished with the spiral of inquiry structure. By modeling the use of this framework as a leader and using it to guide PLC groups, we moved closer to demonstrating “a commitment to working in learning teams, [and] to having a strong moral purpose grounded in ensuring the success of all learners” (McGregor et al., 2017). Ensuring that teachers understand this framework will take time. An emphasis on scanning for understanding is a way that moves beyond quantitative data analysis, helps us connect to students’ experiences, and, I would argue, has an impact on participants’ hearts.

With continued commitment to this structure, I scanned my staff at the end of the year to gain a better understanding of their experience within their PLCs and whether the Slide Deck was a helpful tool in making their learning visible and keeping them focussed. Approximately two thirds of the staff participated in the survey and of those, 71% indicated they did not find this tool helpful. Many felt it was too restrictive and they were unsure how to use it. Sharing this information with staff will again illustrate my own commitment to being curious.

The Next Steps in the Journey

I return to the initial rationale for why establishing a culture of curiosity is so essential. The OECD has recognized that global competency comprised of skills, knowledge and attitudes is something all citizens will need to thrive in “culturally diverse and digitally-connected communities in which we will work and socialize” (2017, p. 1). In fact, the Programme for International student Assessment (PISA) 2018 will include a single scale to measure this competency in 15 year olds around the world. It will be important to find out what our students know about global issues, as well as what type of learning environments could best develop attitudes of openness towards diverse cultures as well as empathy and flexibility. In short, teachers will need to be reflective, curious and open to designing these new environments with the support and guidance from school leadership.

It will be important to continue to use the spiral Framework as a guide for myself and my staff, and to maintain alignment in our work. Rather than leave staff to explore freely with their own inquiries, we will work together through the data and begin to formulate hunches in smaller, self-selected PLC groups; seeking to address what our students are telling us through a spiral of inquiry.

To ensure we stay on track, I will also distribute the leadership so that PLCs are better supported. Teachers were led this year almost exclusively by me as their principal. Some districts have school-based Inquiry Coordinators. To help build capacity and knowledge both vice principals attended the Summer Institute at the University of British Columbia to learn more about inquiry-informed and innovative practices. As well, I have changed the Leader Groups’ configuration and job descriptions to focus on inquiry. We are seeking ways to build their knowledge so they can lead the PLC groups confidently through the inquiry framework.

Regardless of the structure used, or the amount of support provided to people, changing learning environments is complex. John MacBeath (2013) in Leading Learning in a World of Change best describes why this work is so tough: for many teachers,

their views of teaching are shaped by their own experience , so they return to the places of their past… They may feel they have no need to ‘discover’ the classroom or to see it with new eyes because they are already so familiar with the territory. (p. 89)

As staff make their thinking visible, talk about teaching beliefs, and openly share stories with each other we become a community of learners.

In staff meetings, we will continue focusing on the learning for all through sharing the progress of PLC learning partnerships. We will continue to work through the School Plan in visible ways as it is a living document and will change to reflect the work from the PLC partnerships. Leaders will also bring common learning needs from the PLCs to share in staff meetings. This will align PLCs’ work with the students in our classrooms; echoed in the broader plan for the whole school. All of this work will come from the themes that are emerging from the initial student scan and the OECD Principles (2012) to which this data speaks. Checking to see whether we have made enough of a difference will involve a cycle back to the descriptions of each of the principles found in The Nature of Learning (Dumont et al., 2012).

Despite the wonders that continue to rattle around in my heart and head, I will move into next year strong in my resolve to stay curious. My staff and I will make our way from what we have always known to the murky depths of the unknown, buoyed by the possibility of creating better learning experiences for our students and for ourselves.

References

British Columbia Ministry of Education. (2015). Curriculum and core competencies. Retrieved from the British Columbia Ministry of Education website: https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/competencies

Cameron, C., & Gregory, K. (2014). Rethinking letter grades: A five-step approach for aligning letter grades to learning standards. Winnipeg, MB: Portage & Main.

Dufour, R. (2004, May). What Is a "Professional Learning Community"? Retrieved June, 2017, from http://teach.oetc.org/files/archives/ProfLrngCom_0.pdf

Dweck, C. (2016). Mindset: the new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books.

Dumont, H., Istance, D. & Benavides, F. (Eds.). (2012). The nature of learning: Using research to inspire practice. A practitioner's guide. Paris: OECD.

Halbert, J., & Kaser, L. (2015). Spirals of inquiry: For equity and quality. Vancouver, BC: BC Principals' & Vice-Principals' Association.

Kools, M., & Stoll, L. (2016). What Makes a School a Learning Organization? OECD Education Working Paper, No 137. Paris: OECD.

LeFevre, D., Timperley, H., & Ell, F. (2016). Curriculum and Pedagogy: The future of teacher professional learning and the development of adaptive expertise. In Wyse, D, Hayward, L, Pandya, J (Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment (pp. 309-324). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

MacBeath, J. (2013). Leading learning in a world of change. In OECD, Leadership for 21st Century Learning. Paris: OECD.

McGregor, C., Halbert, J., & Kaser, L. (2017). Leading for Learning: District leaders as networked change agents. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2015). Schooling Redesigned : Towards innovative learning systems. Paris: OECD.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Dumont, H., Istance, D., & Benvides, F. (eds.) (2012). The Nature of Learning:Using Research to Inspire Practice. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/50300814.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2017). Global competency for an inclusive world. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/education/Global-competency-for-an-inclusive-world.pdf

Resources for growth and learning mindsets. (n.d.). Retrieved November 03, 2017, from https://www.mindsetkit.org/

Reynolds, L., & Birdwell, J. (2015). Mind over matter. London, UK: Demos Publications. Retrieved from https://www.demos.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Mind-Over-Matter.pdf

Ritchard, R., Church, M., & Morrison, K. (2011). Making thinking visible. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Wagamese, R. (2016). Embers: One Ojibway's meditations. Madeira Park, BC: Douglas & McIntyre.

Congrats Barb- so proud of you