Transformative Educational Leadership Journal | ISSUE: Fall 2017

What does it take to be a teacher who scans their learners, learning environment, and their own practice with curiosity and a eagerness to learn? Using the characteristics of an Inquiry Teacher, as defined in her upcoming book with Trevor Mackenzie, Rebecca Bathurst-Hunt frames the transformations that she and her students experienced.

By Rebecca Bathurst-Hunt

My journey as an inquiry teacher has shifted my practice to make a difference for learners. Over the past year, the most meaningful shifts emerged when I embraced the traits of an inquiry teacher (Bathurst-Hunt & MacKenzie, in press):

- I am curious,

- I go outside to come back inside,

- I know my students and my curriculum,

- I am playful,

- I reflect and revise as I go,

- I teach slow and I am passionate.

The traits of an inquiry teacher have supported me to change my practice and empowered me to share my journey with educational colleagues.

Inviting and creating change in our practice can be one of the most

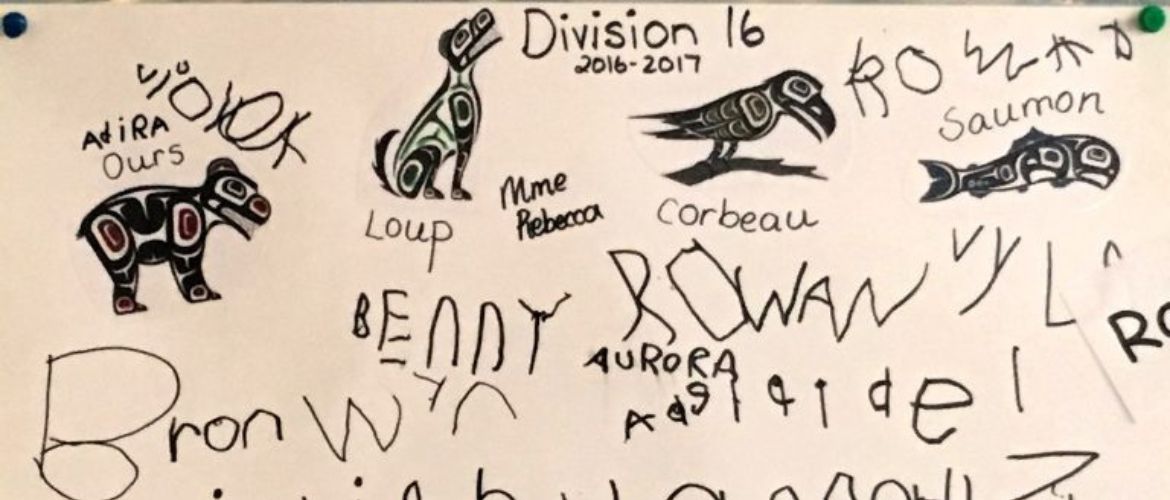

Figure 1. I illustrated this sketchnote (Ovenell-Carter, 2015) to help bring to life some aspects of my journey adding columnar artwork from the Greater Victoria School District’s Aboriginal Education Enhancement Agreement, The Spirit of Alliances, (Aboriginal Nations Education Council, 2013).

beneficial learning experiences for educators. Being playful, passionate, curious, and reflective allows us to dabble in shifting our practices. In doing so we:

- honour ourselves as educators

- invite ourselves to take time and to teach slow, and

- open ourselves to question and wonder.

These traits and experiences shape us, as educators, and define us as inquiry teachers who continue to learn from others, know our students and curriculum, and take risks with our practices to enhance student learning (Bathurst-Hunt & MacKenzie, in press).

Here is my story framed with the traits of an inquiry teacher. Using this framework enables me to discuss the transformation in my classroom in a way that others can more easily apply to their own contexts.

An inquiry teacher is curious

I am a curious educator, curious about where my learners come from, how they learn best, what they are passionate about, and where their learning will take them. My essential question last year was, How can I best support students in learning how they learn best? This curiosity led me to self-regulation for learning (Butler, Schnellert & Perry, 2017), learning targets (Wiliam, 2015), Indigenous connections (Laura Tait presentation; FNESC Principles; Storywork Pedagogy), and processes of understanding self and identity.

An inquiry teacher goes outside to come back inside

Looking outside my classroom practice allows me to network so I can learn from others and return to my classroom with new ideas. Last year my networking included pursuing graduate work at Vancouver Island University’s Master of Education in Leadership program. Judy Halbert and Linda Kaser introduced me to the Spiral of Inquiry (2016) which guided me in understanding how my learners truly learn best. Connecting with a diverse group of educators across the province, country and world enabled me to shift my practice by trying different approaches grounded in learning, research and others’ experiences.

An inquiry teacher knows their students and their curriculum

After an inspiring summer of learning, I settled into my classroom with my Kindergarten learners with building relationships as my number one goal. We played, tinkered, investigated, practiced mindfulness, ventured outdoors and shared our hearts. In order to better know my students I spent a lot of time scanning (Halbert & Kaser, 2016).

During this phase, I noticed my learners:

- were quite unaware of how they could meet their own needs as a learner,

- needed support in self-regulation and self-awareness, and

- had very little experience and knowledge about Indigenous culture and people.

I realized that:

- determining how each individual learns best would benefit the group,

- linking teachings of Indigenous culture and land into the learning process and experiences was essential, and

- learners’ needs aligned nicely with British Columbia’s Core Competencies (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2015).

An inquiry teacher is playful

Without any guarantees as to what would work and what would not, I started experimenting with different ideas and research methods that I had learned from other teachers who had already incorporated Indigenous perspectives, self-regulated learning (Butler, et al., 2017) and Core Competencies (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2015) into their teaching. From The Spirit of Alliances (Aboriginal Nations Educational Council, 2013), the Greater Victoria School District’s Aboriginal Enhancement Agreement, I learned about the teachings of four local animals and how they are linked to social-emotional learning (Butler et al., 2017). The Esquimalt and Songhees Nations describe these teachings:

- Bear teaches about self-regulation, acting with intention from the heart,

- Salmon teaches about growth mindset (Dweck, 2007), collaboration and never giving up,

- Wolf teaches about relationships, and

- Raven teaches that everyone possesses a special gift and has a way of being creative with their thinking (Aboriginal Nations Educational Council, 2013).

The four animals provided a framework that would support my learners in their learning. Knowing that Kindergartners need playfulness, I decided to introduce the ideas with a story written by school and District counsellor Laurie Bayly. Students then played with a provocation, an area set up to provoke thinking and spark curiosities, which gave them space to create and explore connections and build understanding. Witnessing children interacting with artefacts to create stories and adventures was exciting and powerful; I realized they were creating personal attachments to the animals through play.

Figure 2. First Image –Four stones that represent Greater Victoria School District Artwork, Second Image –The Four Stones book written by Laurie Bayly. Third Image: A small world provocation in my classroom to provoke playful connections and ideas.

To further deepen their budding understanding, each animal’s teaching and meaning was introduced, one lesson at a time. We shared stories of times in our lives when we were like each animal. Every lesson ended with a journal entry.

Figure 3. A student learner’s journal entry about how she was like the Salmon. “I tried a green water slide, I was a little bit scared but Salmon tells me to try.”

Once we established a shared and strong understanding of the Spirit of Alliances, complete with five-year-old-friendly descriptions of each animal’s teachings, we signed a class agreement. The agreement signified that, throughout our Kindergarten year, we would be working towards embodying the teachings of the four animals.

Figure 4. Above: Our class agreement, signed by each member of our class. Below: A child’s artwork, created at home, to represent the colours associated with each animal. This is a clear example of the depth of learners’ connections to classroom lessons, the land, and the heart-felt significance of the animals described in The Spirit of Alliances (Aboriginal Nations Educational Council, 2013).

Next, we began setting positive learning intentions based on the traits of each animal. I scaffolded this process, with lots of modeling and sharing of intentions. Some examples of Kindergarten-level intentions are:

- Bear – Keeping my hands to myself and my body calm

- Raven – Sharing my special gift of being able to puzzles with a friend

- Wolf – Being kind to a friend during exploration play time

- Salmon – Not giving up on the monkey bars during recess

Each morning we had mindfulness and reflection time, starting with poses and breathing. Our mindfulness poses were various postures linked with stories and animals to encourage deep breathing, focused minds and reflection. After these postures, I would walk the learners through reflecting on yesterday’s intentions before shifting gears and setting new learning intentions for the day. Gathered at the carpet, whilst children shared their intentions, I would move their names on a board as a visual cue to represent their commitment for the day. This board was a great visual tool to reference during the day, to ensure actions were being taken with the respective lenses and focus of the animals.

Figure 5. Left: Our class intention setting board. Four art pieces are by artist Sue Coleman; Right: Two classmates during our mindfulness reflective time.

An inquiry teacher reflects & revises as they go

Each day, we set positive learning intentions by using the four animals. Wanting to connect learning meaningfully to BC’s redesigned curriculum, I focused on the Core Competencies (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2015) and found an overwhelming number of connections between them and The Spirit of Alliances work (Aboriginal Nations Educational Council, 2013).

During this time I found pause to reflect on our progress. I found myself wondering

- how we could make the learning more visible throughout our day.

- how to give learners time to reflect on their decisions, communicate their intentions and actions, and articulate their reasoning behind their intentions.

- about the opportunity to weave our work with formative assessment and documentation, using our digital portfolios on FreshGrade™, a digital assessment platform.

- if families felt included in our dialogue so I added more snapshots and assessments on FreshGrade™ to ensure their involvement.

- how I would tie the work into term overviews and report cards.

Some of these wonders were answered when I conducted one-on-one reflections with each learner, reinforcing the importance of providing them with a chance to reflect so I could hear and notice how their thinking had changed. These reflections, essentially self-assessments, provided rich and powerful fuel for their learning. Here is an excerpt from one learner’s reflection.

Figure 6. One student learner’s reflections from a one on one reflective session.

During these interviews with students, my instincts were confirmed; our work was transformative. Learners closely held Indigenous perspectives to their hearts as they reflected on the history of our land.

An inquiry teacher teaches slowly

Learners were confidently setting learning intentions and reflecting on their personal and social needs. As their confidence and understanding grew, I felt we could go further with our intention setting by slowing down enough to connect with our intentions throughout our day. This space emerged in a few ways:

Name Tags

Learners used name tags to independently demonstrate their intention for each day. They would move the paper clip on their name tags to track changes throughout the day, visually mapping their intentions. This typically happened after whole group intention setting, during snack time.

Figure 7. Student learner’s name tag at their table spot.

Check-Ins

We took more time with whole group circle and journal check-in reflections. This pace helped keep conversations focussed on our intentions, as a group and for individual reflection. As a group, we enjoyed journaling and sharing our progress towards meeting intentions.

Documentation

I found ways to introduce more opportunities and time for documentation. Learners used iPads™ to capture and document themselves working towards their intentions. They used Pic Collage™ to create visuals of themselves reaching their intentions. I encouraged learners to share their process with the whole group and on the FreshGrade™

Learners even used GoPros™ as a  documentation tool to capture videos of themselves learning; they would then highlight portions of their footage during a sharing circle explaining their learning intention and showing how it was met. This tool was new, empowering and allowing students to reflect on their learning as never before.

documentation tool to capture videos of themselves learning; they would then highlight portions of their footage during a sharing circle explaining their learning intention and showing how it was met. This tool was new, empowering and allowing students to reflect on their learning as never before.

Here is an example of one reflection:

Hazel was excited one morning to share her special gift of enjoying rainy day adventures. Her intention was to be like the Raven and she jumped with enthusiasm when she asked to wear the GoPro™ outside. She wanted to wear the GoPro™ to capture herself being like Raven in sharing her special gift and ideas for fun rainy day adventures. She shared this clip with the whole group and reflected on how she had practiced this special gift for going outdoors by playing in the rain often with her family. When Hazel decided to use the GoPro™ to capture herself as a learner she demonstrated that she recognized her positive personal strengths and the footage allowed her to communicate these strengths to her peers.

Core Competencies

Learning aligned with the concepts and teachings of BC’s Core Competencies (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2015) by pairing the teachings from the four animals with each statement. The two frameworks are strikingly similar in focus; being aware of how you learn and interact as a learner. We began doing reflections, using the Core  Competencies (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2015) language, in addition to the four animals’ language, throughout the day or after specific learning projects. Ongoing reflections and self-assessments to use throughout the second and third terms were created and shared. We reflected on learning and shared thoughts with families.

Competencies (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2015) language, in addition to the four animals’ language, throughout the day or after specific learning projects. Ongoing reflections and self-assessments to use throughout the second and third terms were created and shared. We reflected on learning and shared thoughts with families.

Individual Activities

Discussions about setting learning intentions for each day provided an opportunity to focus on the benefit of setting intentions for other parts of the day as well. These intentions were sometimes different from the day’s overall intention, and that was positive. One Kindergarten learner stated,  “You can be more than one animal in one day and that’s actually really good! Because then you are even more thoughtful”. Intentions were based on one of four local animals but would also need to connect to one of the criteria pieces for the specific activity. Connecting this to a familiar activity was a successful place for learners to start. They began with setting an intention specifically for a journal activity.

“You can be more than one animal in one day and that’s actually really good! Because then you are even more thoughtful”. Intentions were based on one of four local animals but would also need to connect to one of the criteria pieces for the specific activity. Connecting this to a familiar activity was a successful place for learners to start. They began with setting an intention specifically for a journal activity.

Most children decided, for example, that they would be like the Salmon(persevering) on one criteria piece using the statement: I am  going to be like the Salmon and work on remembering to end my writing with a period. Sticky notes were used to signify that it was connected to the statement chosen from a list of co-constructed criteria.

going to be like the Salmon and work on remembering to end my writing with a period. Sticky notes were used to signify that it was connected to the statement chosen from a list of co-constructed criteria.

An inquiry teacher is passionate

Throughout the year, as learning evolved and change emerged, I realized that this shift was powerful for both myself and for my learners. This learning process is extremely valuable for an educator. I wondered about the value of sharing my learning, just as I had been asking my learners to share theirs. After all, we learn in community and I am part of a larger professional community of learners. While I am passionate about my learners’ learning, I’m also passionate about supporting the professional learning of colleagues and, as a result, their students.

I began to share with colleagues, near and far, what I was trying and doing as well as how my practice was changing. I shared with my school, district and provincial colleagues, both casually and formally. The change that began to emerge from these opportunities was transformational. Other educators started to validate our work, asking to be involved, to hear more, and for permission try it themselves. I urged them to seek guidance to ensure their work was meaningful and connected to their local land and Indigenous peoples. Slowly, a ripple grew. This felt exciting and empowering. I realized that creating change in my practice would benefit both my learners and myself, but I had not imagined the impact it could have for others. My passion grew stronger.

My journey as an Inquiry Teacher has been transformational for my practice and the experiences of my learners, and that transformation has created ripples in the practice of many of my colleagues. I learned that leadership emerges in many ways. I realized that any educator can create a ripple by being passionate and sharing their work. I remembered that transformation emerges from curiosity, being able to go outside and come back in, knowing both students and curriculum, being playful, being able to reflect and revise, teaching slow and being passionate. These traits make me an inquiry teacher (Bathurst-Hunt & MacKenzie, in press). As an inquiry teacher I am capable of creating transformational change.

References

- Aboriginal Nations Education Council. (2013). The spirit of alliances: A journey of good hearts and good minds. Retrieved from the Greater Victoria School District website: https://documents.sd61.bc.ca/ANED/educationalResources/SpiritOfAlliances/Aboriginal_Education_Enhancement_Agreement_2013-2018_GVSD.pdf

- Archibald, J. (2008). Indigenous storywork: Educating the heart, mind, body and spirit. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

- Bathurst-Hunt, R., & MacKenzie, T. (in press). Inquiry mindset. Irvine, CA: EdTechTeam Press.

- British Columbia Ministry of Education. (2015). Curriculum and core competencies. Retrieved from the British Columbia Ministry of Education website: https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/competencies

- Butler, D., Schnellert, L., & Perry, N. (2017). Developing self-regulating learners. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- Dweck, C. (2007). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

- First Nations Education Steering Committee. (n.d.). Retrieved from: http://www.fnesc.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/PUB-LFP-POSTER-Principles-of-Learning-First-Peoples-poster-11x17.pdf

- Halbert, J., & Kaser, L. (2016). Spirals of inquiry: For equity and quality. Vancouver, BC: British Columbia Principals’ & Vice-Principals’ Association.

- Ovenell-Carter, B. (2015, November). Taking visual notes with sketchnotes. Workshop presented at the EdTechTeam Summit, Victoria, BC.

- Tait, L. (2016). Lecture on Aboriginal Education. Personal Collection of L. Tait, School District 68, Nanaimo, BC.

- Wiliam, D. & Leahy, S. (2015). Embedding formative assessment: Practical techniques for k-12 classsrooms. West Palm Beach, FL: Learning Sciences International.

Thanks for making such a powerful contribution Rebecca.

Hi there,

You make reference to Carol Dweck and her use of Indigenous understanding of salmon to represent growth mindset. I’m wondering if you can point me in the direction of that quote in her book.

Thank you.