Transformative Educational Leadership Journal | ISSUE: Spring 2018

There is no doubt there are different levels of leadership and that within any given school there will be individuals who have characteristics of a traditional leader; but it is the emerging leader, the influencer, who takes center stage in this story. By Rachelle Buch GoncalvesIt is the start to a new school year and excitement is in the air. Teachers have returned to school with enthusiasm and energy to start afresh. As the teachers congregate in the Library Commons, the hub of the school, the energy is palpable. Suddenly, the energy shifts as the principal begins to speak; there is a new direction for professional learning that is going to shape the district vision. For those who have already been introduced to this new, visionary approach to professional learning it is an exciting announcement, while for others it feels that this announcement has completely derailed their autonomy. The teachers thoughts of “yet another top-down decision” is apparent in their body language. The side conversations begin to ramp up as teachers voice their frustration, anger, and, ultimately, their resignation from the entire decision. Yet, in this crowd there is a teacher librarian who will be an influential leader within the school, across the district, and in time, across the province.

Why should school leaders care about informal leadership?

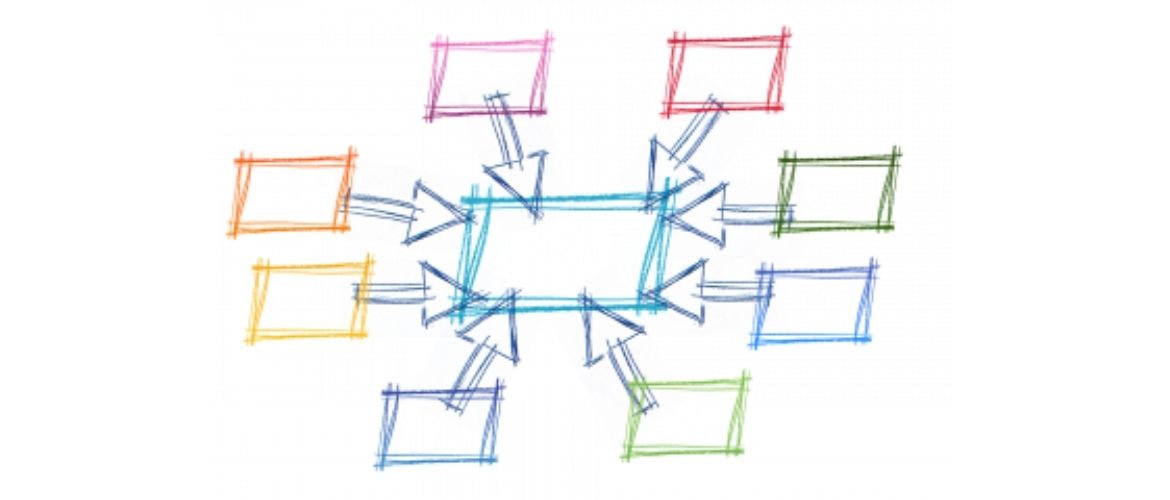

Leadership, in the traditional sense, is defined as “the office or position of a leader” (Leadership, [Def. 1] 2018) which places authority on those we recognize in positions of power. When the notion of leadership arises there is often a vision of hierarchy. Society traditionally sees authority sitting atop the triangle, observing and directing from above. Traditionally the example sees the superintendent, administration, and teachers building the triangle in a top-down design. What is changing in our world is the urgency for a flattening out of this triangle and shifting to a model of shared leadership. The term guanxi, originating from China, is loosely translated to mean “connections, networks and community relationships” (Pontefract, 2016, p. 136). Perhaps these relationships are the key to meaningful and sustainable change in our schools. What if, we focussed on leadership as “the act or instance of leading” (Leadership, [Def. 3] 2018), regardless of job title? What would that do for learning? What would it do for system change? This article shares the journey of a rural school district in British Columbia, but it could be the same story in your very own school district. The superintendent had a vision of transformational change that was systemic and meaningful, and she made a decision that introduced the vehicle for innovation for everyone’s learning. One could argue that this decision was made from the top of the triangle, as many decisions are made in traditional leadership models, but it was this initial, bold move that set change in motion. Change needs to be continuous to keep learning in schools in line with the changes in our world. What, then, is the critical element to this learning? Inquiry. In the rural district mentioned above, the superintendent’s introduction of an inquiry model meant there was a platform for the entire district. Specifically, the Spirals of Inquiry model developed by Linda Kaser and Judy Halbert (2013) was about to change the professional learning and leadership culture across the district. The superintendent, principals, vice-principals, teachers and education assistants were all introduced to the framework for professional learning. There is no doubt there are different levels of leadership and that within any given school there will be individuals who have characteristics of a traditional leader; but it is the emerging leader, the influencer, who takes center stage in this story. Whether informal or formal, the opportunity for leadership and learning through inquiry, can have a powerful influence. We often hear how critical lifelong learning is and that learning something new keeps us alive and thriving. In fact, changing our mindset to embrace challenge and to approach our learning with a growth mindset (Dweck, 2008) is an opportunity in itself. The important takeaway is that opportunity can appear in many forms. Intentional professional learning has been a critical component to transformation for this district. Who grabbed onto this opportunity to lead the way? Who is this emerging leader? The teacher-librarian. In a small, rural district with only three secondary schools, there has been impressive innovation in leadership through inquiry. One of the first steps was making the position of teacher-librarian a priority across the district where the role included building a vision of library commons and inquiry driven learning. It cannot be denied that the culture of professional learning, and the driving force of inquiry is embraced by the teacher-librarian. In fact, the unassuming bookworm is no longer sitting idle. Influenced by a collaborative inquiry model and a shared leadership model, the teacher-librarian helped to transform professional learning through inquiry.What do school leaders need to know about inquiry, learning, and leadership?

It is no longer acceptable for the education system to provide reproducible knowledge (OECD, 2015) when learners require the skills to create and add value to the world in which they live. One could argue that this knowledge creation could be coined innovation, with education providing the opportunity for modelling these requirements and supporting their development (Katz, Earl, & Jaafar, 2009a). Innovation in education, however, is not a new or novel concept. In fact, educators are continually presented with the next best strategy or newest pedagogical shift that will revolutionize their learning and the learning of their students. Why is it, then, that these innovative practices are still grappling to take hold, even decades after they are first introduced? Simply put, leadership. How these innovative practices are brought forward and implemented make an incredible difference to the level of acceptance within a school or school district. Education is notorious for being an “innovation hostile environment” where innovative learning practices are typically the exception to the rule rather than the norm (OECD, 2015, p. 6). Despite the fact that there are many areas within a school where this innovation is resisted, often the school library commons, and teacher-librarians specifically, embrace innovation and act as school leaders, change agents, and catalysts for school improvement (Oberg, 2009). Hord, Rutherford, Hulling, and Hall (2006) define a change agent’s role as supporting, assisting, nurturing, encouraging, persuading, and pushing people to change, to adopt an innovation, and to use it in their daily work. This profile of a change agent succinctly describes teacher-librarians and their daily work, suggesting that teacher-librarians are excellent candidates for bringing about learning innovations and change in leadership. What is the critical element, then, for this innovation to begin taking hold? The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) outlines three innovation dimensions in their paper Schooling Redesigned, which include strong learning leadership, strong design with vision for transforming systems, and leadership which is informed by reflective practice (2015). School leaders need to take note of the power of developing leadership capacity within their schools, the importance of a district vision and model for transformation, and the influence of professional learning networks for continual growth.Leadership Capacity: Action vs. Title

Fundamentally, leadership is a verb which implies action; therefore, a title without action is meaningless. Often, to clarify leadership roles, we add adjectives to the title such as instructional, transformational, distributed, or teacher, but these adjectives can add to the confusion. No matter what is added, however, it can be argued that the one adjective that is not welcome in the leadership role is one of a heroic leader (Mulford, 2008). The leader who comes in to save the day, ready to bless the organization with their wisdom, is seldom welcome or accepted. For this reason, rather than recognizing a singular leader in a traditional leadership hierarchy, the model should be one of collective leadership as we move away from heroic constructs and recognise the benefits of distributed, shared leadership (OECD, 2015, p. 26). In fact, those that are most effective are the individuals who are not only called leaders, but actually lead (Couros, 2018). Does effective leadership, then, even require a title? Or can teachers who formally, or informally, take on leadership roles make change happen? Lieberman & Miller (2004) describe teacher leadership as “the development, support, and nurturance of teachers who assume leadership in their schools” (p. 154). The OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (2015) suggests that “what counts increasingly are the versatilists who are able to apply depth of skill to a progressively widening scope of situations and experiences, gaining new competencies, building relationships, and assuming new roles” (p. 3). These emerging leaders are constantly learning and growing, by positioning and repositioning themselves in a fast changing world (OECD, 2015, p. 3) which is precisely what we hope for our learners.Shared Leadership

Andreas Schleicher explains in The OECD Handbook for Innovative Learning Environments (OECD, 2017) that “if there has been one lesson learnt about innovating education, it is that teachers, schools and local administrators should not just be involved in the implementation of educational change but they should have a central role in its design” (, p. 3). This is not to say that a shift towards shared leadership is about mutual decision making, rather teachers “become more engaged, productive, connected and collaborative so that [they] feel part of the equation and not simply a number in a database” (Pontefract, 2013, p. 169). Ownership, and the involvement of all stakeholders, plays an integral role in leadership and innovation. When those involved in leadership, formal or informal in capacity, shift their mindset from ‘everyone else but me’ to ‘everyone including me’, the collective efforts begin to make a difference for our learners (New Zealand Ministry of Education, 2018; Timperley, 2012). When characterizing an effective change agent Harada and Hughes-Hassell (2007) include moral purpose, personal vision, commitment, capacity for inquiry, high abstract thinking skills, knowledge and mastery, collaboration, resiliency, and interpersonal skills. Regardless of the role, or the title that holds their place on the hierarchical structure of leadership, leaders are curious. Leaders want to contribute; they will find a way to do so, and they are “key to creating and sustaining momentum for system change” (Harris, 2017, 51). As Couros (2018) says, “We can all do better, but when in positions of leadership, legacy is created by what the people you serve do”. This is the goal we strive for, innovative practice to empower our leaders and learners “to make informed leadership decisions and to engage in design constantly informed by evaluative thinking” (OECD, 2015, p. 21).District Vision/Model

Schleicher (OECD, 2017) explains that there needs to be robust frameworks and sound knowledge about what works to empower effective innovators and game changers (p. 3). Timperley (2011) further suggests that a key to effective professional learning lies in the need “to be motivated by a need to know, not someone else’s desire to tell” (p. 14). A framework which provides a common structure for professional learning and transformational change, while providing autonomy and ownership, can be a game changer. Leading educational players provide academic research to support those looking to innovate educational practice and leadership. An ethnographic study of 25 teacher leaders across five schools suggests that support for teachers as leaders is critical. In fact, Beachum and Dentith (2004) recommend “specific school structures and organizational patterns, particular processes and identities and deliberate use of outside resources with consistent, strong community relationships” (p.1) as the foundation for creating a culture of teacher leaders and school transformation. Each of these recommendations are recognized as pillars of success in the inquiry leadership frameworks in this section. The Spirals of Inquiry is an action research based model from Kaser and Halbert (2013). Ziegler defines action research as “an intentional systematic method of inquiry used by a group of practitioner-researchers who reflect and act on the real-life problems encountered in their own practice” (2001, p. 3). The New Zealand Ministry of Education (2017) explains that, “inquiry as a process is all about being willing to take risks, to be wrong, to fail in your endeavours and then change direction and start again” (para. 3). Teachers can often be heard declaring that their professional autonomy is of great importance and needs to be protected. Inquiry provides this opportunity for all staff by allowing them to identify a focus in their everyday work, create a sense of agency, and lead to change by placing the ownership and responsibility in their hands. In fact, “engaging in an evidence-informed inquiry process puts responsibility on the professionals to work collaboratively towards change and improvement in teaching practice” (New Zealand Ministry of Education, 2014, p.17). In addition to the discussion surrounding leadership in the previous sections, the New Zealand Ministry of Education (2018) surmises that “by doing the work, by engaging in the spirals of inquiry, the whole process becomes the leadership of change” (para. 2). Having this common framework for professional learning across the school district, for all levels of staff, including support staff, teachers, administrators, and district staff, develops a common language and understanding of the process which creates community on a new level.Community, Connections and Networks

For those individuals or groups who choose to learn only from ‘experts’ or ‘institutions’ there is no doubt that they are missing out on some of the best learning that can be garnered: that of learning from a network. When, as education professionals, we open ourselves up to learning from our network, the possibilities are endless. In Flat Army: Creating a Connected and Engaged Organization businessman Charles Lee explains that he “store[s] [his] knowledge in his network” (Pontefract, 2013, p. 136). As educational leaders, our knowledge also needs to be stored in a network and educational transformation needs to harness the energy and intellect found in the community connections of these networks. As learning is dependent on the motivation of the learner, it is imperative that there is a common purpose amongst a network (OECD, 2015, p. 21) for engagement to occur.What can school leaders do about transforming learning and leadership?

When looking at systemic transformation in education it is advisable to design the environment in which to foster qualities, capabilities, and opportunities for all leaders. An example of such a dynamic is underway in British Columbia’s Okanagan Similkameen School District, a small, rural district where formal leadership has introduced a common framework for professional learning — the Spirals of Inquiry. This framework encourages professionals to take a curiosity mindset (Timperley, 2011, p.xviii), critical for systemic change. How School District 53 (SD53) uses the Spiral shows a commitment to system learning and transformation.Informal Leadership Opportunities

The initial vision of transformation and shared leadership began with the superintendent, and has grown organically since its inception nearly four years ago. At the onset of this visioning process, teachers, administrators, school board members, and parents were invited to a workshop to determine what values would be at the heart of the District vision. This informal opportunity provided teachers, without titles of leadership, to be included in a process of great value.Network Leaders

At a District level, positions were created to lead networks organized around Aboriginal Education, Technology Integration in Elementary and Secondary, Student Engagement, Social Emotional Learning and Early Learning. Teachers were then encouraged to join a network to develop their practice and extend networking within the district. The structure required accountability, fiscally and with evidence of growth, and varied in identity with budgets used for resources, teacher coverage, collaborative time, etc. Most networks met outside of the school day to extend the budget as teacher time is the most costly factor; however, school visitations from the network leader and meetings during the school day were not uncommon. The network leaders played an important role in the development of these networks, which as Katz, Earl and Jaafar (2009b) suggest, is one of seven key enablers of Network Learning Communities. Once these networks were developed, network leaders were then tasked with facilitating each of the remaining seven components including: “purpose and focus, relationships, collaboration, inquiry, leadership, accountability, and capacity building and support” (Katz, Earl, & Jaafar, 2009b, p. 12). Using these components as a framework, the learning was intended to reach beyond the network leaders and facilitate learning for the district as a whole. The initial reach of the network was limited; however as Katz, Earl and Jaafar (2009b) explain:Building capacity depends on intentionally fostering and developing the opportunities for members to examine their existing beliefs and challenge what they do against new ideas, new knowledge, new skills, and even new dispositions. When networks are focused on learning, they intentionally seek out and/or create activities, people, and opportunities to push them beyond the status quo (p. 15).As the Network Leader role evolved, the vision of transforming leadership on a systemic level became more visible. Encouraging professional learning among staff across the district increased sharing between teachers, subject areas and schools. In SD53, this deliberate action of creating networks and perseverance by the superintendent, has created a flourishing network of professionals who are empowered to lead, regardless of role or title.

Inquiry Leaders

A pivotal step in the journey for SD53 has been the rebranding of network leadership. Systemic change is evident in the district as department heads were replaced with Inquiry Leaders, accountable to support and facilitate inquiry at the school level for staff. A school inquiry is the focus for all, but Inquiry Leaders help guide and facilitate inquiry at a more personal level for each staff member. This shift demonstrates the value placed on collaborative inquiry as well as on shared school leadership. At Southern Okanagan Secondary School, one of three secondary schools in SD53, Inquiry Leaders support networks in Assessment, Indigenous Education, Cross-curricular Learning, and Social Emotional Learning. All staff self-select a network of interest and create an inquiry question to guide their own practice. The school plan, monthly inquiry sessions, collaboration, and teacher and administration professional growth plans are connected to the inquiry work. The framework and network support the inquiry and the inquiry supports learning.Networking Beyond the District

As capacity builds, staff become more confident in their work and the potential to share with a larger audience emerges. The benefits of sharing beyond the comfort of the school can be an unnerving yet valuable experience for many people. Although SD53 teachers do not necessarily feel like ‘the expert,’ the reality is that they are building capacity in an area that is innovative and creating change. The unassuming leaders, including the teacher-librarian from the vignette above, are transforming what learning and leading look like and the work is worth sharing. A network teacher explains the importance of this shared leadership: The network brings together educators of all levels and then puts them all on the same level, making us teaching and learning resources for each other. We are all learners; we are all drivers of change; we are all important in the system. (Harris, 2017, para.52) This recognition of value, regardless of title, is critical to share because it shows how we are bridging research to the practice of system change.What does all this mean for school leaders interested in using inquiry as a framework for transforming professional learning and leadership?

When embarking on the Spiral of Inquiry as a model for system transformation, we discovered that, as with all change, it takes commitment. Here are six points of reflection:- Go with the goers. Change is difficult enough to initiate so start by working with those who are open to change.

- Fail forward. Accept and embrace failure as a means of moving ahead; some of the greatest work comes out of persistence.

- Be patient. Change takes time, it is not going to happen overnight, but it is well worth the effort.

- Support the work. Actions are stronger than words; engage in the work, fund the work, and provide time for the work.

- Trust the process. Do not give up on the framework too quickly; refer to considerations two and three.

- Share. Create networks, create and share knowledge, become the expert.

Beachum, F. & Dentith, A. (2004). Teacher leaders creating cultures of school renewal and transformation. Educational Forum, 68, 3, p. 276-286. Retrieved from https://eric-ed-gov.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/?id=EJ724873

Couros, G. (January 21, 2018). The Principal of Change: Stories of learning and leading. The one answer to all questions in education. [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://georgecouros.ca/blog/archives/8003

Dweck, C. S. (2008). Mindset: the new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books.

Halbert, J., & Kaser, L. (2013). Spirals of inquiry for equity and quality. Vancouver, BC: The BC Principals’ & Vice-Principals’ Association.

Harada, V.H., & Hughes-Hassell, S. (2007). Facing the reform challenge: Teacher-librarians as change agents. Teacher Librarian, 35(2), 8-13. Retrieved from http://login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest -com.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/docview/224886309?accountid=14474

Harris, A. (2017). Teachers leading reform through inquiry learning networks. TEL Journal. May 2017. Retrieved from https://teljournal.educ.ubc.ca /2017/05/teachers-leading-reform-through-inquiry-learning-networks/

Hord, S. M., Rutherford, W. L., Hulling, L., & Hall, G. (2006). Taking charge of change (Rev. ed.). Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

Katz, S., Earl, L. M., & Jaafar, S. B. (2009b). How networked learning communities work. In Building and connecting learning communities: The power of networks for school improvement (pp. 7-22). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi: 10.4135/9781452219196.n2

Leadership. [Def 1.] (2018). In Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/leadership?utm_campaign=sd&utm_medium=serp&utm_source=jsonld

Leadership. [Def 2.] (2018). In Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/leadership?utm_campaign=sd&utm_medium=serp&utm_source=jsonld

Leadership. [Def 3.] (2018). In Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/leadership?utm_campaign=sd&utm_medium=serp&utm_source=jsonld

Lieberman, A., & Miller, L. (2004). Teacher leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass/Wiley.

Mulford, B. (2008). The leadership challenge: Improving learning in schools. Australian Council for Educational Research. Retrieved from https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=aer

New Zealand Ministry of Education. (2014, November). The future design of professional learning and development. Retrieved from http://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/ Initiatives/PLD/The-Future-Design-of-PLD.pdf

New Zealand Ministry of Education. (2016, March 21). Teaching as inquiry: A refresher. Education Gazette-Education in New Zealand, 95(5). Retrieved from https://gazette.education.govt.nz /articles/teaching-as-inquiry-a-refresher/

New Zealand Ministry of Education. (2018, March 7). Leadership and the spiral of inquiry. Retrieved from http://www.educationalleaders.govt.nz/Leading-learning /Spiral-of-inquiry-leaders-leading-learning/Leadership-and-the-spiral-of-inquiry

Oberg, D. (2009). Libraries in Schools: Essential Contexts for Studying Organizational Change and Culture. Library Trends,58(1), 9-25. doi:10.1353/lib.0.0072

OECD. (2015). Schooling redesigned: Towards innovative learning systems. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264245914-en

OECD. (2017). The OECD handbook for innovative learning environments. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264277274-en

Pontefract, D. (2013). Flat army: Creating a connected and engaged organization. City, State/Province: Jossey-Bass.

South Okanagan Similkameen Teachers’ Union. (2018, February). [PDF] Survey of TIM Time. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

Timperley, H. (2011). Realizing the power of professional learning. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

Timperley, H. (2012, March 5). Building professional capability in schooling improvement. Retrieved from citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download? doi=10.1.1.1011. 9201&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Ziegler, M. (2001). Improving practice through action research. Adult Learning, 12(1), 3-4.